Again, last week was the eighteenth anniversary of 9/11 and the start of a larger movement by the public-safety community to fix its communications systems. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) authorized a 10-MHz swath of 700-MHz spectrum for public-safety broadband with the Public Safety Spectrum Trust (PSST) being the license-holder. Shortly thereafter, the PSST and a new organization known as the Public Safety Alliance (PSA) began lobbying those in Congress to convince them this new spectrum was not enough and pointing out that the “D Block,” a 10-MHz portion of spectrum adjacent to the public-safety spectrum, had not been picked up at auction by any commercial carrier because it was designated as a combination commercial and public-safety cooperative venture and needed to be added to the existing public-safety broadband spectrum.

The PSA, along with some cellular vendors, Land Mobile Radio Vendors (LMR), and others began canvasing Congress in earnest in 2009. As you may know, it took until 2012 to convince Congress to pass the Middle-Class Tax-Relief Bill of 2012, and in February of 2012 this bill was signed into law. Title VI of the bill created FirstNet, provided a small amount of funding for Next-Generation 9-1-1 (NG911), and more money for research and development. FirstNet is real today and continues to expand and improve with each passing month. However, the public-safety community is now faced with other matters that will require Congress and/or the FCC and the Executive Branch of the U.S. Government to take care of some lingering issues.

Congress is back in session, and its members’ attention is needed to address several items that have been languishing in the Halls of Congress for too long. My list of these items and then a discussion of each follows.

- T-Band (470-512 MHz) spectrum: Congress decreed this spectrum must be returned to the FCC within a few years from now.

- Next-Generation 9-1-1 (NG911): Improving 9-1-1 to realize its potential with FirstNet. The bill and funding await votes.

- 4.9-GHz: WiFi-like spectrum for public safety, which is even more important now that FirstNet is in place.

- 6-GHz microwave: Band sharing-fixed microwave and unlicensed use coexistence?

- Rural Broadband: Required of FirstNet, but federal assistance is needed to fix the digital divide.

These are the issues I think are the most important for Congress, the FCC, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and the Executive Branch to address, and address quickly. Further, if I were a member of Congress, I would also introduce a bill that would enforce a “hands-off” public-safety spectrum policy. No sharing, no reselling.

T-Band

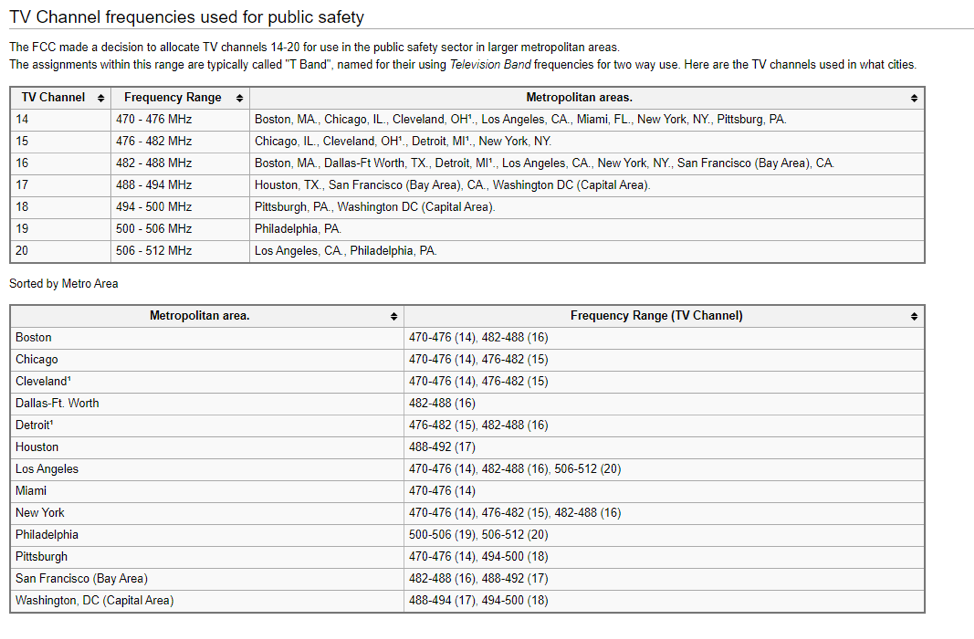

This should be the easiest issue since the give-back can be reversed with a simple vote of Congress. When the T-Band was included as a “give-back” in the bill that created FirstNet, Congress thought this shared TV spectrum would be worth $billions since it was in the existing TV bands. This has been proven incorrect. Since the spectrum is used by public safety in only eleven metro areas, and since not all of the spectrum is used in all of the eleven metros, its value is, in my estimation, around $zero for any other use. The National Public Safety Telecommunications Council (NPSTC) T-Band update report listed TV stations using T-Band TV channels in the United States excluding the eleven metro areas. The number of high-powered stations was pegged at 325 and hundreds more were classified by the FCC as low-powered.

This means T-Band spectrum could never be considered nationwide spectrum for broadband or any other use unless these 325-plus TV stations were ordered to change channels. When you look at the eleven metro areas, it is evident that all the TV channels within the 470–512-MHz band, seven of them (channels 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20) are not used in all eleven cities. However, each city has access to between one and three of the seven channels. Thus, it is evident that this spectrum is not suitable for much of anything except T-Band.

Keeping the T-Band in place for the eleven metro areas should be an easy decision for Congress. When you analyze which party has the most voters in each of these cities you find they are spread out between both parties so this should not be a partisan play by either side of the aisle. There were several attempts to allow public safety to keep the T-Band spectrum in the 2017-2018 Congress in both the House and the Senate. Today there is a single bill in the House, H.R. 451, “Don’t’ Break Up the T-Band act of 2019.” This bill needs to be passed quickly.

I say “quickly” because agencies using the T-Band are not permitted to upgrade or modify their licenses without a huge hassle, and the bill creating FirstNet did not provide for either spectrum to which these departments could be relocated or funds to do so. This is becoming critical since if there was a place for them to go, it would cost $billions and take two-to-three years or more to complete.

I believe part of the problem is that many members of Congress were elected after the lobbying efforts and passing of the FirstNet bill. They don’t seem to understand that this is a critical issue that needs to be addressed immediately. Another issue I see is that even though the public-safety community and now the Government Accounting Office (GAO) are recommending against terminating public-safety’s use of the T-Band, it seems this matter is not being recognized as being important. Yet it is the right thing to do and the T-Band bill could probably be passed by both houses of Congress in a minimal amount of time.

NG911

FirstNet is the next generation of public-safety communications from the dispatch center out to first responders. NG911 is the “network” that will be used to feed voice, data, messaging, videos, and still pictures from citizens reporting an incident to dispatch centers (now called Emergency Communications Centers, ECCs). Together, NG911 and FirstNet will revolutionize public-safety communications. By forwarding better, vetted input from citizens over FirstNet, those responding to an incident will have more complete information and a better idea of what they are heading into. In essence, these two networks, along with LMR, are the future of public-safety communications. Their combined use will reduce response times, provide better services to citizens, and better protect first responders.

Apparently, there are no proposed bills in either house of Congress even though past attempts to pass such a measure were introduced in the last Congress and carried a price tag of $12billion. This money may or may not be enough to deploy NG911 on a nationwide basis but it will make it easier for states, counties, and cities to make up the difference. This should also be a non-partisan issue since it effects both red and blue states and will provide better public-safety responses to their citizens regardless of political affiliation. Passing bills to address NG911 and the T-Band give-back should be worth some votes to incumbents running for re-election to Congress in 2020.

4.9-GHz Public-Safety Spectrum

This segment of public-safety spectrum is 50-MHz wide and was initially designated for on-scene data communications. Over time, many departments experimented with using this spectrum for incident-level events and found it was also suitable for providing backhaul for fixed cameras and more. In a previous Advocate, I discussed the issues with using FirstNet or any commercial cellular broadband network for fixed cameras. Cellular systems were designed to ensure each cell sector would have some unused capacity reserved for people or vehicles that come into the cell sector from a different cell site. Using fixed cameras with cellular changes the mathematics that determine the amount of unused capacity to be retained and how much traffic is currently within a segment.

4.9-GHz has become an important portion of public-safety spectrum because it is being used for backhaul for fixed cameras and point-to-point communications. And it appears to be ideal spectrum for public safety to use to form a bubble around its vehicles to enable others to access FirstNet even when their devices are not FirstNet-enabled. The FCC continues to play with the idea that this spectrum should be shared with another service or two, or perhaps even be used by unlicensed operators. With the advent of WiFi 6 with its increases in speed and performance, I believe 4.9-GHz spectrum holds tremendous value for public safety and it should not be used for both public safety and other services. The 4.9-GHz spectrum should remain a portion of the exclusive public-safety pool of available spectrum.

6-GHz Spectrum Sharing

It appears the FCC has become enamored with the idea that it can open up spectrum for unlicensed use without regard for its current use. The FCC will require unlicensed users to register with a database intended to control where in the band they can operate without creating interference. Existing 6-GHz use consists of point-to-point microwave systems used by public safety, industrial companies, and many other types of microwave traffic. The idea that both licensed and unlicensed users can co-exist in a segment of spectrum that is already highly developed make no sense to me.

Most 6-GHz microwave being used today was installed when the FCC put the AWS (2-GHz) spectrum on the auction block for cellular and broadband purposes. During the transition, the next logical location for point-to-point microwave was the 6-GHz band. In many areas today, it is almost impossible to find a 6-GHz channel that is not in use. Further, the next band, the 12-GHz band, is becoming crowded. Moving from 2 GHz to 6 GHz required more “hops,” and going beyond that to 12 GHz will require even more hops.

My final point is that if there is interference between licensed 6-GHz users today, the FCC database can be accessed to determine where interference may be coming from and the two affected organizations can usually work out and solve the problem. If one user is unlicensed, there is no way find out who is responsible for the interference. Since much of the 6-GHz microwave traffic is considered mission-critical in nature, I have a real problem with trusting a database to allocate unused portions of the spectrum in this band. I urge the FCC and Congress to put an end to the belief that spectrum can be shared regardless of who else is using it.

Would the NTIA permit unlicensed users to co-exist with Secret Service radio channels? Many of their channels are not heavily used most of the time in many areas of the United States. I don’t believe for a minute the Secret Service would be in favor of sharing its spectrum, so why does the FCC think it is acceptable to jeopardize 6-GHz point-to-point systems in use today?

Rural Broadband

Many of you know I consider one of the greatest challenges for broadband is to cover rural America. FirstNet is required by law to extend coverage to rural areas but it cannot afford to cover every inch of the United States. Priority has to be established based on population per square mile to justify new cell sites since they cost so much to build.

Meanwhile, the federal government, FCC, NTIA, Rural Utilities Service (RUS), and others offer grants and loans for rural broadband deployments. In our work with counties we have categorized twenty-six different grants and loans available from multiple agencies. The issues I have with this piecemeal funding are that it takes a long time to prepare a grant request, many agencies offering grants still seem to believe fiber to the home or farm is the best way to roll out broadband, and most of the grants do not support on-going costs for insurance, damage, or even normal operating expenses.

Some states have been successful in stepping in to assist areas that need broadband. However, to my knowledge, none of these agencies or states are working with FirstNet (Built with AT&T) even though FirstNet is an obvious partner for many of these grants and roll-outs. In the House, a bill known as H.R. 2661, “The Rural Broadband Act,” would consolidate all available grants under the auspices of a single organization that would work with states, counties, and tribes, but so far, this bill does not appear to be gaining much traction. This is a shame since continuing down the road we are on with multiple agencies with multiple grants does not address the big picture. Combining this money into a rural broadband fund would make it quicker and easier to extend broadband into rural America.

Introducing New Legislation

As mentioned at the beginning of this Advocate, if I were in Congress (not at all interested), I would introduce a bill that would prohibit both the FCC and NTIA from requiring any type of takeback, sharing, or reallocation of existing-public safety spectrum. Much of the public-safety spectrum is already intermingled with business and industrial companies so taking it away from public safety would mean also taking it away from the other users within the band. Another reason to limit public-safety spectrum to public-safety use is that LMR systems (using public-safety spectrum) provide off-network or simplex operation at incident scenes. Broadband does not yet have this capability and it appears that the 3GPP attempt to introduce simplex will not provide coverage that is even close to the range provided by LMR handhelds today. Further, the 3GPP broadband simplex will not be able to penetrate walls or make its way into sub-basements where other forms of communications are not possible.

Finally, we have to ask what today’s public-safety communications are good for. They cannot be used for broadband unless you want to carry a cell phone that looks like a brick. Even then, since there are not enough contiguous channels to bundle together for broadband, it would be close to impossible to make it work. The FCC and others within the federal government seem to think broadband data is the key to everything, but those of us who have been around the block a few times have come to understand that it takes different types of wireless communications for broadband to be to useful consumers, public safety, paging companies, taxis, utilities, and so much more. If you want to see how crowded our spectrum is, visit the NTIA website and order a copy of its wall chart of spectrum allocations. When it arrives, take out a magnifying glass to see all the users and spectrum allocated for each segment. Until FirstNet becomes the only network needed (if it does), all public-safety spectrum must be protected.

Winding Down

It was my intention to write a segment about Assured Wireless’ HPUE (High-Power User Equipment) that I think will be such an important addition to the FirstNet product line. Many of you know the portion of Band 14 licensed to FirstNet is under Part 90 as is all public-safety spectrum rather than Part 22 commercial wireless service rules. As a result, Band 14 and only Band 14 is the only broadband spectrum that can be used for mobile equipment that transmits at power levels of up to 1.25 watts (typical broadband devices transmit in the neighborhood of 250 Milliwatts).

This is important for public-safety agencies that use FirstNet for the purpose of increasing range and throughput in areas where coverage for their devices is spotty and it is important for covering citizens and public-safety personnel in rural areas. The higher power will enable faster data speeds farther from a cell tower, which will in turn help reduce the number of cell sites required in underpopulated areas.

Because I ran long writing about what the federal government needs to do to assist the public-safety community and thus citizens who vote them back in or out of office, I have decided to table discussion of Access Wireless’ HPUE until next week.

FirstNet is encouraging new and different ways to look at broadband services. FirstNet gives AT&T the latitude to identify the best possible products and services for the public-safety community while the FirstNet Authority remains engaged and active in future enhancements to the network, devices, and applications that will continue to rank FirstNet as a “must-have” within the public-safety community.

Until next week

Andrew M. Seybold

©2019, Andrew Seybold Inc.

You failed to include TV-15 (476 – 482) used in Los Angeles for Public Safety. It is allocated to Los Angeles County for the LA-RICS Digital Trunk Radio System.

Gene, you are correct, I did fail to mention LA-RICS and TV-15, it was not part of the NPTSC report so I neglected to update the information and I stand corrected.