An Open Letter to Those Who Oversee, Plan, Build, and Operate the FirstNet Network

This Advocate is not about blame, it is about mistakes all of us made, where we are today, and any plans there may be to get back on track.

The public-safety community needed, wanted, and fought for a public-safety broadband network with nationwide communications capabilities between and among all first responders who use FirstNet (Built with AT&T).

The network build-out is almost finished and it is better than any of us expected…except for one crucial capability. It is essential for all public-safety agencies to be able to communicate with all first responders and agencies on FirstNet regardless of where they are as long as they are in range of the network. Public safety needs this capability now, but it is not possible today. What are the plans to complete this part of the mission as defined by public safety? (community)

Mistakes Made by All

When a wireless or even wired network is built, it is built by experienced people who understand how networks work and what is needed to build and maintain the “pipe” that is the network. These people have been building wireless networks for transporting information for a long time now and they know what they are doing.

While the shape FirstNet would take was being discussed in Washington, DC, one model consisted of a situation when at least one lane of an Interstate highway needed to be cleared. When public safety needs complete and uncontested access to a highway, they have it. Likewise, when public safety needs complete and uncontested access to the data highway, they will have it. Public safety expected this same level of access to be provided by the FirstNet network.

Over time, everything fell into place. FirstNet was created and signed into law, the FirstNet board of directors was appointed and began holding meetings, and the Public Safety Advisory Committee (PSAC) that reports to the directors was established. During all this activity, the focus was always on the network. Board members who had been involved in cellular network build-outs before led the charge. Board members from public safety who had, for the most part, been using their own Land Mobile Radio (LMR) networks for many years weighed in with suggestions for how the network should work and who should be able, for example, to control the priority levels of public-safety users in a given area during an incident.

All was well, or was it? Nothing about this process seemed to be wrong or out of sync with the common goal of a nationwide public-safety broadband network.

However, all but a very few overlooked the content aspect of the network. This is understandable since those who build networks do so for customers and customers determine what their networks will be used for and what they need in the way of content. Public safety also missed considerations for content because they were accustomed to having a network in place and using it for Push-To-Talk (PTT) voice. Both groups were focused on what they do best. One built networks and the other used networks.

What was not taken into consideration was what, exactly, would run over the network. The premise of FirstNet from early on was to build a nationwide broadband network public-safety personnel could access no matter where they were, even outside their jurisdiction.

This new network was intended to solve communications problems that had become evident during a number of major incidents that high-lighted the interoperability issue first responders had been facing for years. Multiple agencies responding to assist other agencies were finding that their land mobile radios were on different portions of spectrum so they were not able to communicate with others on the scene. FirstNet was to become the solution. From network design to implementation, the emphasis was on building a “smart pipe” capable of passing voice and data among every first responder on the network regardless of their location. From the beginning, both those who build broadband networks and those who use LMR networks were so focused on the network itself that content that would ride on the network was overlooked.

Cellular/broadband network operators build a network and their customers determine how the network will be used. Public safety uses networks built by others. For this project, the emphasis was on building the network to carry communications once it was operational. With a few exceptions that are included in the FirstNet Authority contract, content was considered to be the purview of users and it was assumed that content would take care of itself once the network was in operation.

Except for a very few, no one recognized how this focus would affect the performance of the network. Part 1 of the project was to put a nationwide broadband network in place. Part 2, in which public safety called for nationwide, common applications, was overlooked. Part 2 had been included to make sure everyone on the new network could communicate with other first responders on the network. In all fairness, those who oversaw the network build-out and those who built it were building a network to be used by others (customers) for information sharing.

Two organizations, the Public Safety Communications Research (PSCR) Division of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the National Public Safety Telecommunications Council (NPSTC) were aware of the need for nationwide voice and data communications on FirstNet. To fill this need, they set out to have a standard developed for voice and data implementation across the network, coast to coast, and border to border. A single push-to-talk standard would enable every agency, vehicle, and first responder to communicate with each other wherever they are. After the need for a push-to-talk standard was raised, both the network team and the first responders agreed it was a good idea.

Good Intentions

These organizations’ intentions were good and on the money with what would be needed from day one. However, not factored into the task was the amount of time it would take to define the standard, draft it, and then publish it. After publication of the standard, more time would be needed for vendors to add the application to their devices.

The task of producing this new push-to-talk standard was undertaken by the 3GPP, the worldwide standards organization that developed broadband network standards. At the time, the 3GPP had only worked with network standards for LTE, and LTE and 5G today. This challenge to develop a PTT application standard would be the 3GPP’s first venture into application standards for commercial networks. In addition, 3GPP membership is made up mostly of people who are concerned with broadband standards. These include network operators, vendors, and others, many of whom had no idea what push-to-talk is all about or why PTT is important for broadband networks when they already support dial-up voice and text messaging. The PSCR took on the responsibility of ensuring at least some of the members of the PTT taskforce had a firm understanding of the importance of push-to-talk, and they did the best they could to speed up the process.

Going back to the highway example, what we had was one truck (the network) that had already started down the reserved lane and another truck (the PTT standard) that needed to catch up with the first one. The second truck started slower and was not able to maintain the speed necessary to catch up with the first truck.

A Single PTT Standard

Participants PSCR, NPSTC, and others agreed that it was a good idea to have a single PTT standard across the network. However, even before taking the task to the 3GPP, some vendors were providing push-to-talk over cellular (POC) in response to Nextel being sold to Sprint and the end of Nextel’s push-to-talk system. Some broadband vendors, such as Verizon, told me they had no interest in PTT services at the time because it was only a niche market, T-Mobile did not seem to have any interest either, and Sprint decided it needed a PTT service to replace Nextel’s PTT. Since Sprint’s network was a Qualcomm CDMA network, Sprint turned to Qualcomm’s “QChat” for its solution.

At about the same time, Kodiak Networks and several other vendors were coming online but, frankly, PTT over 3G networks was not a compelling competitor to existing PTT systems. It was too slow to connect to other users, volley times were too slow, and the audio wasn’t that great. However, 4G was just beginning to come online and 4G LTE’s speed and low latency compared to 3G made a huge difference in PTT Over Cellular (PTTOC) performance.

For a while, there were several PTT applications vendors vying for the business including Twisted Pair, (purchased by Motorola and renamed WAVE), another PTT vendor (purchased by Motorola that disappeared into the night), and a few others.

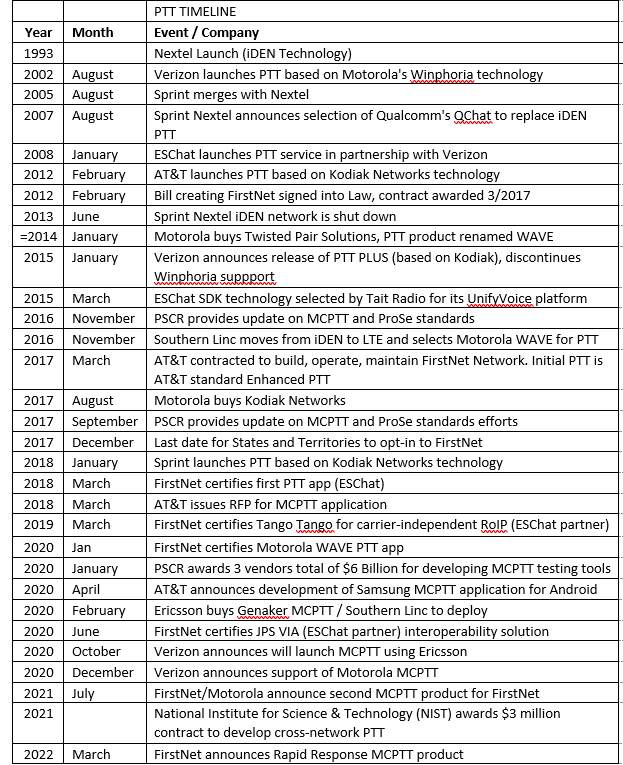

Perhaps to better understand how and why nationwide PTT on FirstNet went off the track, we need to know more about the timeframe and what else was going on during the creation of the PTT standard. Some specifics are noted below but there is a more complete list of dates later in this article.

The Issue

There is no more urgent task or agenda item than 100-percent nationwide Unified Push-to-Talk services for our First responders.

Questions

- Exactly what is the action plan for Unified Push-to-Talk services and who is responsible for following through?

- Who is responsible for completion of the plan?

Below is a list of some significant dates with what was happening in relation to FirstNet PTT.

After the PSCR convinced the 3GPP to develop a standard for broadband PTT, the 3GPP didn’t publish the first PTT standard until it released LTE Revision 13. From that point forward, it has taken much too long for MCPTT to be installed into a single Android device. FirstNet released a second MCPTT announcement in mid-2021 but so far, there is no date for when it can be purchased and put into service.

More recently, FirstNet announced “Rapid Response,” its MCPTT solution.

Several other dates of interest include when FirstNet (Built with AT&T) certified other vendors’ PTT products for use on the network. Comparing these certification dates with MCPTT’s progress on the PTT standard, you will see that by the time MCPTT made its first appearance on FirstNet, the other PTT operators were already well established and at least three had contracts with many agencies from small, local departments up through federal government FirstNet users.

The reported amount of funds awarded to various companies by both PSCR and NIST, have added up quickly and as, far as I can tell, none of these investments have resulted in product or service offerings.

Note: “Announcement date” is not necessarily when the product was shipping, some announced products are not yet shipping or even available.

So far, we have a very robust nationwide network. As of the most recent report, there are more than 3.3 million FirstNet users and the network covers more of the U.S. than expected. The network was built out sooner than expected, and extras such as deployable cell sites and other products and services have been added.

We also have seven or more PTT-over-FirstNet vendors, all vying for customers (seven certified offerings, at least one not certified). We finally have the beginnings of what was intended to be the nationwide PTT standard for the network. So where do we go from here?

- Exactly What Is the Plan?

I believe at a minimum, the following items need to be taken into consideration when developing a plan for nationwide PTT over FirstNet.

- How many of the existing 3.3 million FirstNet users are using PTT over FirstNet?

- Of those, how many also have their LMR PTT systems integrated with their FirstNet PTT?

- How many and which existing vendors account for the majority of FirstNet push-to-talk users?

- How many of these existing PTT customers will move from their current PTT system to a 3GPP-standard platform?

- How much will it cost them to move to a new provider?

- How much will it cost them to re-build their LMR-to-FirstNet integration hardware and software?

- How long will this transition take?

- What incentives will you offer existing PTT customers to change to a new provider?

- What benefits will this new provider offer that existing PTT vendors don’t already provide?

- If agencies do not agree to change PTT vendors, what is the alternative?

- PTT interoperability

- Is there a way to provide multi-vendor PTT interoperability?

- Can it be done without use of a cloud or driving up the per-unit price for FirstNet customers?

- Is there is a way to provide multi-PTT vendor interoperability, how long will it take, and how much will it cost?

- If multi-vendor interoperability requires each PTT vendor or FirstNet user to pay additional PTT fees, how much will these fees be and what, exactly, will be included?

- Which two PTT vendors with the most FirstNet clients worked with FirstNet on integration with a 3GPP PTT application?

- Would there be a price increase for existing PTT users?

- Who would be responsible for the interoperability portion of this solution?

- If it will be an existing PTT vendor, would this choice help or hinder the interoperability solution?

And this is only a partial list of the issues.

Before a solution is implemented, the are two huge issues that must be resolved. First, when will nationwide PTT interoperability be available for the first-responder community? Second, what will agencies be charged for each PTT device activated on the system?

What if today’s 3GPP standard on FirstNet could be married to a second vendor’s over-the-top PTT application? Which application promises to have the greatest number of paid customers for the application if it is integrated with land mobile radio systems? How long would that take, when would it be available, and what would the per-device cost be for this service?

Finally

As discussed above, the community that makes up FirstNet has already made a number of mis-steps in how to implement Unified PTT on a nationwide basis. If there is a plan to resolve the issues, let’s do it. If there is no real plan, let’s sit down and figure out what is needed and how soon it can be ready to implement!

Winding Down

The public-safety community needs to have the best possible tools for their safety and the safety of citizens they serve.

Most public-safety professionals depend on the communications devices and networks they use daily, and most of the first-responder community does not want to be communications experts. They want to know that if they use their radio or smartphone when they are in a jam, someone will hear them and respond.

Anyone who has not been in full turn-out gear, with a tank of air on their back and a mask on their face while in a room full of smoke might not fully understand how important good, solid communications can be. This also holds true for law enforcement professionals who find themselves in situations that might not end well, and lest you think paramedics don’t have to worry, keeping their patient alive and sometimes being targets is plenty to worry about. A few years ago, there was a situation where paramedics were called to a residence that had been set up as a trap and a deranged person started shooting at them. Unfortunately, paramedics remain vulnerable to similar circumstances today.

Those of us who work with the public safety community but do not play and active role need to understand that communications tools are a vital part of the lives of those who face dangers. A number of years ago, I was asked to assist a police chief in convincing his city council to fund a new, badly needed radio system. We all gave our talks, but there were still some doubts because it was a lot of money. The chief stood up, went to the front table, unloaded his pistol, laid it on the table, and laid his radio next to the pistol. Then he stated that if he had to choose only one of these two tools, it would be his radio. The final vote to purchase the new radio system was 6-0 in favor!

Some will say I am too focused on nationwide PTT on both FirstNet and integrated into LMR systems. Perhaps this is true. I believe very strongly that we owe our first responders the best possible communications we can give them. I also believe we cannot and should not wait to equip public safety with nationwide Unified PTT on the network and in their hands.

Whatever solution is chosen, it needs to be deployable very soon. It cannot be out of reach pricewise for any agency or first responder, and the solution must work everywhere whether within range of a network or not. When I discuss communications with executives and line officers anywhere in the U.S., I am always asked what is happening with nationwide PTT and why don’t they have it yet. I don’t have an answer for them, but I understand their asking for soething that many of them believed would come with the nationwide public-safety broadband network. I think we owe them these tools and we need to provide them as soon as possible.

Until next week…

Andrew M. Seybold

©2022, Andrew Seybold, Inc.

Andy, here’s some help with your answers.

If all you have is a hammer, even a screw looks like a nail . . .

Too bad that those who understood LTE modulation and bandwidth requirements for PTT did not say something (or were ignored) early-on in the FirstNet process. LTE protocol is not efficient for PTT. It was conceived as a revenue upgrade mechanism to cellular communications (single subscriber unit ESN) and leveraged Internet connectivity (bit-based billing) over existing licensed frequencies.

Large groups of participating PTT units swamp available bandwidth and, because of FDMA limitations, overwhelm inbound channels. This condition is exacerbated in major event conditions with limited cell towers. 5G bumps (5x) channelization by use of more bandwidth, but is not available in 100MHz chunks in the lower cellular frequencies so actual bandwidth improvement is limited. Carrier aggregation is a network rather than an RF accommodation. Band 14 on its own is an effective 10MHz 2-way street – PERIOD.

Current ‘MCPTT’ apps must treat each PTT press as a repeated message or stream to each channel participant. LTE was not designed for group calling. The entire LTE assignment and billing infrastructure requires design change and is counter productive to the recent 5G eNodeB EUTRA network distribution upgrades.

It was a stroke of business genius for AT&T to offer immediate use of their commercial network and incorporate Band 14 as a shared ‘secure’ unified network for public safety. Sorry to say to FIRSTNET purveyors of universal PTT over LTE, had you taken the original approach of making Band 14 a ‘stand-alone’ and unique public safety network, PTT might have been incorporated as a core feature. I believe that type of approach gave us P.25 which, by its vocoder mechanism, is 8-10x more frequency efficient for voice communications than LTE.

Keep on pounding and don’t hold your breath . . .

Andy, I always enjoy reading your insights and observations and you are spot on with this one. I believe the rapid pace of the buildout of the network (which was a great thing, but somewhat unexpected) contributed to the problems you point out. The good thing is we now have an opportunity to play “catch-up”, and must do so, to provide our first responders with a true nationwide, interoperable network. Thank you for all of your efforts