First and foremost, I hope everyone stayed safe during the holidays and many of our first responders received their first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine. A number of things that will impact the public-safety community and its communications systems have developed since the last issue of the Advocate. Rather than trying to cram everything into this first 2021 issue, I will focus on the repeal of the T-Band giveback this week and other items next week.

Some topics I will save until next week include the impact of the recent bombing in Nashville, the latest developments in the public-safety community’s fight to retake control of 4.9-GHz spectrum, what I would like to see from the next FCC term, some interesting new products and services, and my 2021 “must-have” list for critical and public-safety communications.

Repeal of T-Band Giveback

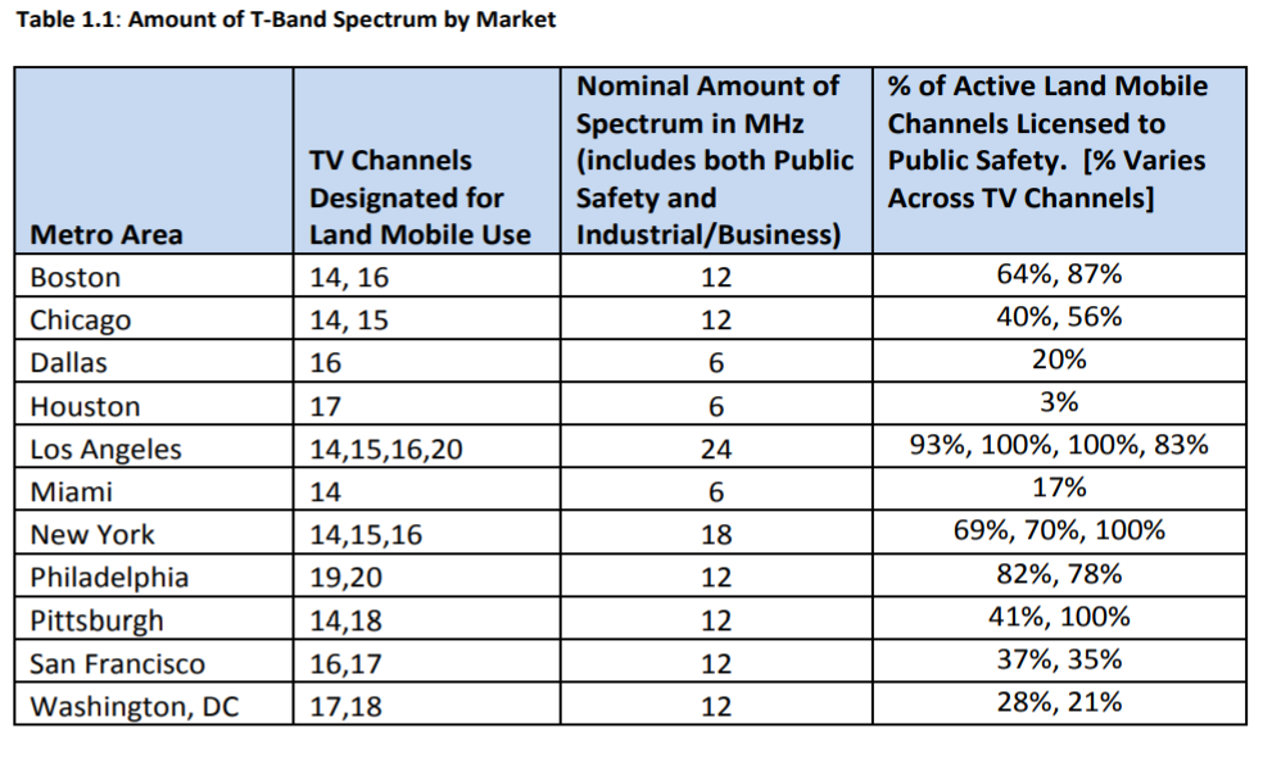

As many of you know, there was jubilation within the public-safety community when the bill that included formation of FirstNet was signed in 2012. That is until we came to the condition that, in ten years, eleven major metropolitan areas and their surrounding suburbs were to lose public-safety spectrum along with some businesses using spectrum previously allocated to TV stations. This 470–512-MHz spectrum had been broken into 6-MHz swaths to accommodate TV stations. Some of these blocks were assigned to public-safety agencies in major metro areas and some to business users. This T-Band spectrum is shared spectrum that would otherwise serve TV channels 14-20.

Congress was convinced that if it took this spectrum back from the public-safety agencies that relied on it, it could bring in $Billions when auctioned in ten years (2022). Some felt since Congress was “gifting” public safety an additional 10 MHz of spectrum in the sought-after 700-MHz band, public safety could simply vacate the T-Band. Those same members of Congress seemed to believe the hype that ten years into the future, FirstNet would be able to simply absorb all the radio traffic currently on T-Band systems. As it turns out, these assumptions were faulty from the beginning and many within the public-safety community recognized that fact.

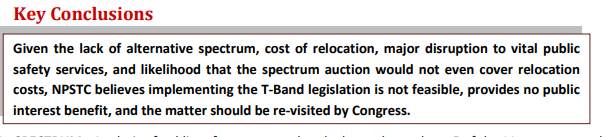

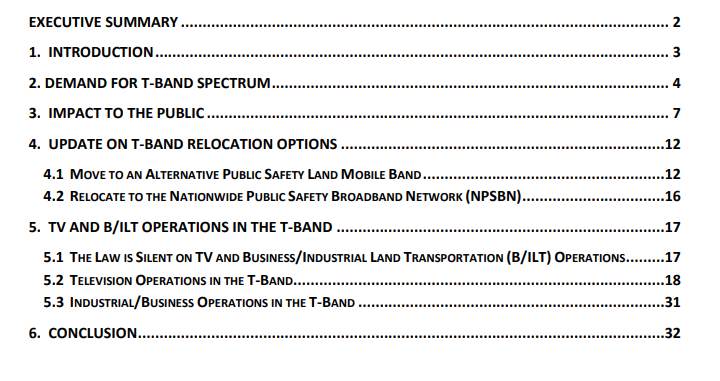

The National Public Safety Telecommunications Council (NPSTC) was the first public-safety organization to step up and provide documentation showing how much of this spectrum was in use, how important it was to public safety, and that there was no other suitable spectrum available for T-Band users. Further, if there was other spectrum, the move would cost public safety, the federal government, or some combination thereof, $Billions and finally, a move from the T-Band to new networks on new spectrum could not be completed in the specified time.

NPSTC published its first report only fourteen months after the bill was signed into law. This report ran sixty-nine pages and it provided detailed analyses of how many agencies were using the T-Band and how many base stations, mobiles, and portables were in use. Then it presented a series of in-depth spectrum and cost analyses proving beyond a doubt that requiring T-Band users to pack up their radios and move elsewhere in the spectrum would cost a fortune and take much longer than the allotted time. And even if there was other spectrum, the loss of the T-Band could endanger citizens served by public-safety agencies in the eleven metro areas and cause additional risk to first responders.

NPTSC followed this excellent report with a second report at the end of May 2016. Below is the index from that report and, as you can see, it built on the first report and included the Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network (NPSBN, FirstNet), which at that point was still in the design and early RFP stages at The FirstNet Authority.

Section 4.2

Relocate to the Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network (NPSBN) as outlined on page 16:

“There are many factors jurisdictions with T-Band have to consider. Many of the applicable questions have answers that are unavailable today and still reside somewhere into the future. For example:

• Does the NPSBN have the coverage for my jurisdiction equivalent to or better than the coverage I have on T-Band?

• Is there commercially available mission critical voice over LTE equipment designed to meet the needs of my law enforcement officers, firefighters, emergency medical service personnel, and other local government functions?

• Has the equipment and the network been sufficiently tested in actual public safety tactical environments to warrant the necessary confidence in the system?

• Are the control and operational functions needed by my jurisdiction available with mission critical voice over the NPSBN?

• Is training available for any functions which are different but still acceptable?

• What is the annual cost of moving all my jurisdiction’s T-Band voice traffic to the NPSBN, and are the necessary funds budgeted on a sustained basis?

• How will my agency maintain interoperability with other public safety agencies operating in the 450-470 MHz UHF band (with which I can communicate today on T-Band)?”

It should be noted that the T-Band spectrum was allocated to public safety by the FCC in 1970 after Los Angeles County and others mounted a push to acquire the spectrum. Between 1970 and finalization of the 2012 law that included the return of the T-Band spectrum to the FCC, more than 900 licenses had been issued for T-Band spectrum.

Once the FirstNet bill was approved, the public-safety community came together in an effort to retain its T-Band spectrum. Over the nine years since, a group of T-Band agencies as well as the IAFC, IACP, NSA, APCO, and many others kept the pressure on Congress to rescind the T-Band giveback. Early attempts fell on deaf ears yet no one stopped trying. Year after year, meeting after meeting, article after article, everyone kept at it. A few months ago when the Repeal the T-Band Giveback bill was passed in the House, we thought it would finally be a done deal. Then a single Senator, whose own state would lose public-safety T-Band access in not one but two major cities, decided he would block the bill from being brought to the floor of the Senate.

FCC Chairman Pai had sent several requests to Congress saying the T-Band should remain in the hands of public safety as did the Government Accounting Office (GAO). Time after time, people who were associated with members of Congress or their staffers tried to reach an agreement. Finally, the Repeal the T-Band Giveback bill found its way into the Omnibus spending bill and passed both Houses of Congress only to be held up at the President’s desk for a week or so. It was looking like T-Band cities would face yet another decade of waiting!

Finally, on Sunday, December 27, 2020, the President signed the Omnibus funding bill and the T-Band will remain in the hands of public-safety and business radio users that were also sweating the outcome because they were not mentioned in the T-Band clearing requirements and did not know if they would have to vacate the spectrum and, if so, where they would go.

So many people, organizations, and vendors were involved in this many-year process that it is not possible to give each and every one a shout-out. Suffice it to say that the public-safety community, even those that would not be directly impacted by the T-Band giveback, realized how critical this spectrum had become and continued to provide support.

T-Band Giveback Repeal Is Only the Start

Public-safety agencies in eleven metro areas can breathe a sigh of relief. However, they will need to do a lot of catching up. Some T-Band users were able to find other spectrum and relocated. However, now many T-Band systems need upgrades and the FCC is talking about narrow-banding the spectrum. Most spectrum used by public safety has already gone through narrow-banding, which involves splitting each channel in half, either via digital technology or creation of new channels. The idea behind narrow-banding is to double the number of Land Mobile Radio (LMR) channels in a given portion of spectrum. There are benefits to having access to more unique channels, but there are a number of issues with voice clarity.

Narrow-banding the T-Band is a costly undertaking for agencies that use the spectrum and the FCC should not take this decision lightly. Many departments need to upgrade their systems and, in many cases, expand their coverage. While the T-Band’s fate was unknown, the FCC made it difficult or impossible to even file for changes to existing licenses. Thus, as populations grew in many metro areas and their suburbs, radio systems were not able to expand to cover new population centers.

The last issue facing T-Band users is the rising amount of interference due to the FCC’s decision to auction the 600-MHz band and relocate TV stations to lower in the TV spectrum. This has led to interference to some public-safety T-Band systems, and Los Angeles County and agencies on the East Coast are having additional interference issues. Resolving these issues should be the responsibility of the newest license holder to occupy the spectrum (in other words, the relocated TV station). Now it appears public safety will have to work with the FCC to help mitigate these interference issues.

Agencies that use the T-Band can now look at what they need to do to bring their networks up-to-date and expand them if needed. If the FCC decides narrow-banding is needed, this will add to the expense and delay system upgrades. As with the T-Band relocation, none of the necessary work or equipment will be paid for by the federal government. Public safety will have to find ways to fund their projects and budgets have already been slashed. Perhaps we could do what the Miami Police Chief suggested many years ago—sell advertising on the network. In the future, you might hear a dispatcher say, “The following robbery in process is brought to you by Amazon,” followed by the dispatch.

Since that is not realistic, it behooves every agency to exam the FirstNet private/public partnership and consider tower sharing, backhaul sharing, and other ways to find more funds for agencies that have been making do with what they have for the past nine years!

Observations

I find it interesting that some elected officials do not fully understand what the public-safety community has accomplished and learned from working together for the betterment of the entire public-safety community. It is also striking that the FCC, including the one in charge until January 20 and, to a lesser extent, past FCCs, stopped meeting with public-safety professionals and today there is not a single public-safety professional in residence within the Public Safety and Homeland Security Office (PSHSO) of the FCC. Not since 2007 when Derek Poarch was Chief of the PSHSO bureau under then-Chairman Kevin Martin has there been anyone with direct public-safety experience in the bureau that regulates public safety.

I am hopeful the newly-minted FCC that will be seated after January 20 will once again include public-safety professionals within the bureau and they will take part in the ongoing dialog about how our spectrum is allocated, how it is protected from undo inference, and how it is shared. I also hope the new FCC will treat the critical-communications community, which includes public safety, with the same level of consideration the current FCC has shown those who use spectrum for profit.

Public safety remains dedicated to ensuring those in the field who serve and protect have the communications capabilities they need, when they need them. We have come a very long way with the creation and fielding of FirstNet but there is still much to do including rebuilding the T-Band systems that have had to limp along for nine years, implementing Next-Generation 9-1-1 (NG911) on a nationwide basis, and working toward regaining the 71-percent of broadband spectrum (4.9 GHz) being taken away by current majority-party FCC Commissioners. The new FCC should recognize that when the public-safety community comes together it will fight for what it needs, even if the goal seems out of reach, no matter how long it takes.

The T-Band issues have finally been resolved. However, some agencies that moved off T-Band spectrum lost the ability to communicate with other agencies within their metro areas. I hope those who stuck it out will now be able to bring their networks up to where they would have been had it not been for the nine-year hiatus caused by the U.S. Congress.

Until next week…

Andrew M. Seybold

©2021, Andrew Seybold, Inc.

Be the first to comment on "Public Safety Advocate: T-Band Repeal after Nine Years!"