Last week, several readers pointed out that cloud-based interoperability might not always be best for network-to-network and network-to-Land Mobile Radio (LMR) Push-To-Talk (PTT) interoperability. For example, one reader suggested Los Angeles County (Los Angeles Regional Interoperable Communications System, LA-RICS) and the Los Angeles City Police Department, which are using cloud-based interoperability between them, would be better served if they used direct interconnectivity instead of relying on a remote cloud. I agree, and I should have mentioned that one major vendor could become the only FirstNet-to-LMR interoperability provider. I also neglected to talk about my fear that even if this vendor’s PTT will interoperate with other already-certified FirstNet PTTs, there will be pricing discrepancies between this vendor and other push-to-talk providers that have already amassed a large number of FirstNet/LMR-integrated customers.

Samsung Introduces Interworking Function (IWF)

The good news for push-to-talk interoperability across platforms is that Samsung recently announced the release of its 3GPP-compliant LMR FirstNet/LTE Interworking Function (IWF). More than a year ago, FirstNet (Built with AT&T) introduced FirstNet PTT. FirstNet PTT also meets the 3GPP push-to-talk standard and was also developed by Samsung.

Since then, not much has been added to the product in the way of interoperability capabilities or support for non-Android clients including Apple iOS clients. Therefore, Samsung’s announcement that it is providing IWF-compliant interoperability is good news for those who still believe the 3GPP standard will ultimately be the best solution for broadband/LMR push-to-talk interoperability.

I have often mentioned that it was taking a very long time for someone to offer a 3GPP interoperability software solution. Now we have one (actually, a second IWF system). According to Samsung, this first release is designed primarily to support public safety and it will interface with existing public-safety interfaces including ISSI, DSI, and CSI, which are all used for integration of P25 systems. At some later date, it will provide interfaces to other LMR technologies including Digital Mobile Radio (DMR). However, it is not clear when its PTT application will support iOS and Android devices or if it will provide interfaces to analog FM.

Samsung said its IWF software is provided by Etherstack and indicated that though this initial release is designed to be hosted in data centers, which is recommended, it can also be cloud-based.

Samsung pointed out that while the IWF meets the 3GPP-standard interface, the standard itself leaves interfaces beyond IWF undefined. In the case of public safety, it is expected that IWF will be interfaced with ISSI, DSI, and CSSI. Any agency that wants to interface its LMR system with this IWF software solution will have to have ISSI in its P25 system or pay for ISSI or another standard interface to be installed. (FirstNet (Built with AT&T) already offers FirstNet PTT-to-LMR compatibility using Radio over IP (RoIP).)

This the requirement for ISSI itself could be a stumbling block, depending on whose equipment is being used for the local or regional P25 system. Some public-safety vendors have been known to charge a lot of money for their ISSI interface while some FirstNet-approved push-to-talk vendors offer ISSI interfaces at substantially reduced pricing. At least one other approved vendor offers IWF-compliant interfaces and other methods for connecting to analog FM, P25 conventional, P25 trunked, and DMR systems. Now that Samsung has released its internetworking function, we will see how the public-safety community feels about interfacing their LMR systems to a 3GPP-compliant PTT application.

It should also be noted that at least one approved FirstNet PTT solutions provider offers a much less expensive version of ISSI and has used it to integrate FirstNet/LMR public-safety networks for many agencies.

Much work remains to be done to enable true nationwide fully-interoperable push-to-talk for any and all agencies using FirstNet. I still wonder why it is taking so long to provide a service to the public-safety community that will ensure every agency on the FirstNet network can use push-to-talk to communicate with any other agency on the network.

While I fully understand why especially those providing applications and services (but not necessarily those within the public-safety community) keep telling us it will all come together real soon now. I don’t understand why already-approved push-to-talk vendors that are more than willing to come together aren’t providing hybrid solutions that will essentially solve the interoperability issues. I believe it is possible to put together a set of solutions now to provide the level of nationwide interoperability we need now. Later, these solutions could be modified or updated to include more of the 3GPP standard if warranted.

I am encouraged by Samsung’s announcement that it continues to move forward with its push-to-talk solution and hope it will soon fill in the remaining gaps. Meanwhile, we are awaiting the Motorola version of its 3GPP-standard push-to-talk. When it becomes available, we will learn exactly how it will be implemented and what types of interfaces it will provide for existing LMR networks. And, of course, if both Android and iOS devices will be supported.

Perhaps we are moving closer to delivering interoperable voice communications—a must-have for public-safety agencies and personnel. I will continue to follow all new announcements in hopes that vendors will work together to provide the tools public-safety needs.

Side note: I also learned recently that Motorola announced its digital Ion portable smart radio that delivers full LTE capabilities. The Ion can be used for over-the-air programming and it supports the Android operating system. We need more devices like this one for DMR, all LMR technologies deployed in the United States, and Tetra systems that are widely used in other parts of the world.

Revisiting 6-GHz Microwave Spectrum

When the previous Federal Communications Commision (FCC) began talking about using 6-GHz spectrum for secondary unlicensed users, many expressed concerns about the the band already being heavily used for licensed point-to-point, point-to-multipoint and, in some cases, portable critical-communications microwave systems. The FCC assured us that interference to existing licensed users would be prevented with use of an automated system that determines which portions of spectrum unlicensed WiFi 6 systems could use. Many of us remained skeptical and several filings with the FCC suggested that serious studies and testing should be conducted before ruling to allow unlicensed use of 6-GHz spectrum.

However, the FCC went ahead and authorized unlicensed use of WiFi 6 not only in a portion of the 6-GHz band, but across the entire band. After this approval, many within the government, licensed microwave users, and their associations continued to push back on this dual-use.

In a previous issue of the Advocate, I expressed my concern that even with an automated system determining where unlicensed devices can be used, theoretically without causing interference, interference issues will occur. When interference is experienced in spectrum where unlicensed users are operating, it is next to impossible to determine the source of the interference. On the other hand, it is fairly easy to identify the cause of the interference when all users are licensed. Then, once the source of the interference is identified, the licensed users can work together to resolve the problem.

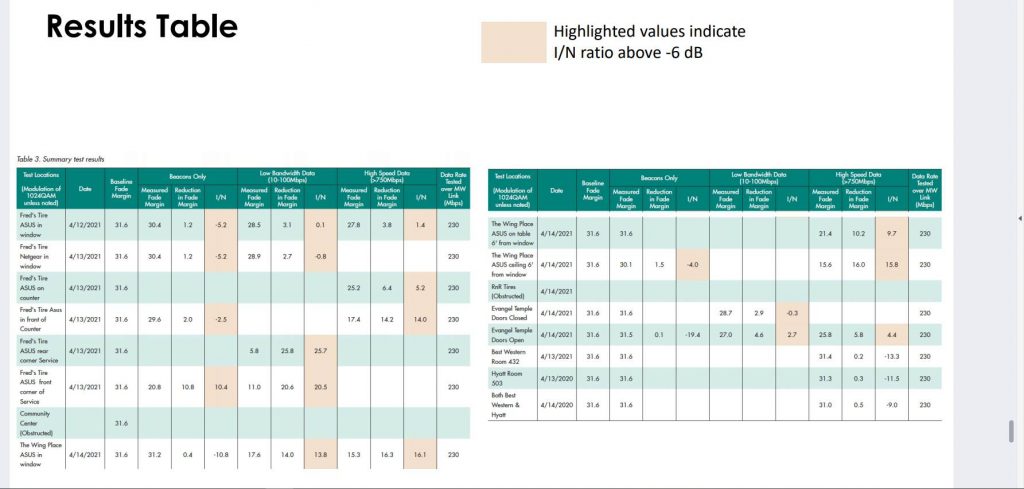

Enter the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI)

On July 15, 2021, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) issued a downloadable report and provided slides to explain its testing in the 6-GHz band. This report is an update to an update of EPRI Low-Power Indoor (LPI) Field Tests. As you will see from my description of EPRI’s testing and methodology, and from the report itself, this is a well laid-out, well-defined set of tests. Results show that even indoor WiFi 6 devices have the potential to interfere with existing microwave systems.

The tests were conducted with Southern Company and the microwave test path was between Columbus, GA and Fortson, GA. FCC type-approved WiFi 6E device signal sources included the ASUS GT-AX11000, Netgear RAXE500 routers, and a Samsung S21 Ultra phone.

Microwave equipment at the two sites included a Nokia WVCE61 in Fortson and an Alcatel-Lucent 95MPR67 in Columbus. Microwave antennas included a Commscope VHLP6-6W8 (CAT A) and a Gabriel DRFB6-59 BSE. In summary, the tests were conducted using top-line equipment and antennas that are FCC-approved, WiFi 6E devices, and an existing microwave path.

The WiFi 6E system was set up for the ASUS router to be the main system router and the Netgear router to be the alternate. The devices“talked” through the router to the Samsung S21 5G Ultra with an Intel AX-210 PCI express module and a Dell laptop (7480) running Windows 10. Another laptop was used to track test results. For this test, the WiFi 6 device domain was 160 MHz of 6-GHz spectrum (6325 to 6345 segment 77). The remainder of the WiFi 6E set-up criteria can be found in the report slides (see below). It appears that every aspect of these tests used standard devices and was well-documented. During the tests, the WiFi system was being used for a variety of tasks including light browsing, video streaming, file transfer, and computer back-up—all normal, routine tasks over the WiFi system.

One interesting finding is that the beacon transmitted by the router is limited to 20 MHz at a rate of 10 Mpbs and it does not take up the entire 120 MHz of the spectrum.

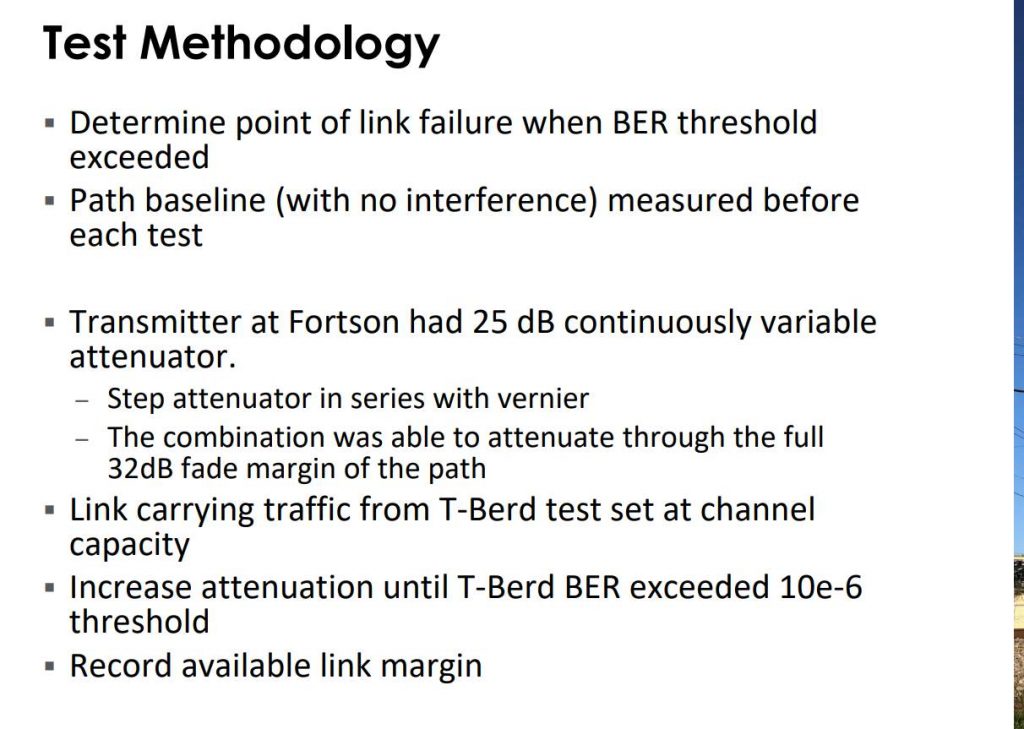

Testing Methodology

Note: (BER) refers to Bit Error Ratio.

At the WiFi 6E test site, the building entry was measured at 6.345 GHz and 21.5 dB, which was attributed to the coated glass at the front of the building. This site was one of several chosen for WiFi 6 testing and set-up and details for each site are included in the presentation. The attention to detail in setting up and verifying each test location is evident from the report, test results, and conclusions as shown in the next two slides:

Comments

The EPRI and Southern Company are to be commended for their testing precision and methodology. It makes me wonder why the previous FCC’s technology people did not undertake this level of testing or why they didn’t at least cooperate with the EPRI and/or other organizations that represent 6-GHz band microwave licenseholders before handing down this FCC ruling on sharing the 6-GHz microwave band.

These results show that the potential for interference even with indoor WiFi 6 systems is higher than the previous FCC believed. As I have said, identifying unlicensed routers and access points that are interfering with existing critical-communications microwave systems could be a long and involved process. It seems the previous FCC administration was more focused on providing additional spectrum for commercial users, unlicensed users, and vendors of unlicensed devices. They did not confirm that they were on firm ground before they approved sharing this band among unlicensed and licensed users.

Hopefully, this study and others will serve as a wake-up call and the new FCC will proceed in a more orderly and cautious manner. Spectrum interference issues will continue to increase as spectrum-sharing catches on. Thankfully, I believe the new FCC Commissioners will take a more balanced approach to spectrum allocations.

Winding Down

As I write this, Hurricane Ida has made landfall as a category four storm. Fires are still raging in the West and one near Tahoe is threatening that area. While the drought continues in the West, the East is inundated with water after the last tropical storm and Tennessee is still recovering from flooding there.

All this means our first responders and those who support FirstNet (Built with AT&T) are spread out all over the nation helping bring these incidents under control and rescuing survivors. The AT&T FirstNet team is in the field with deployables, and other AT&T assets are staged to immediately begin rebuilding damaged cell sites after the storms have passed and it is safe to move into those areas. Of course, other network operators have also staged workers and equipment, and many electric utilities have already put out calls to utility companies in other states for help to restore power service as quickly as possible.

All this, along with the increase in Covid-19 cases because of the Delta variant and people who have chosen not to vaccinate, are stretching all our first responders, including medical staff, to the edge.

Ida came ashore not far from where hurricane Katrina did sixteen years ago to the day. Fortunately, there are a number of differences between then and now. Louisiana has beefed up its dikes to better withstand surges of water, pump capacity has been increased to pump out excessive amounts of rain, and many of the generators have been moved up and out of basements.

FirstNet is arguably the most significant development since Katrina. Sixteen years ago, one of the most obvious issues was the lack of coordinated first-responder communications in New Orleans and surrounding areas. This has been remedied for the most part and this time state, local, and federal agencies have a common broadband communications network. This will make a huge difference and the first-responder community will be able to better coordinate all its activities, especially search and rescue.

The public-safety community rallied together many years before FirstNet was established in 2012. The necessity for interoperable communications during major incidents that require multiple-agency coordination served as a guide for its efforts to convince Washington DC that FirstNet was needed.

There is still a way to go to provide better interoperability between agencies, but today we have a nationwide network and dedicated personnel who can send deployable assets to where they are needed when they are needed.

No one could have foreseen that so many different types of incidents in so many different parts of the United States would happen essentially at the same time. Today, the public-safety community remains united as it works toward improving interoperability and making sure public-safety’s critical communications needs are met today and into the future.

Until next week…

Andrew M. Seybold

©2021, Andrew Seybold, Inc.

Be the first to comment on "Public Safety Advocate: Good News for Push-To-Talk Interoperability?, Bad News for 6-GHz Microwave"