The United Kingdom press and some in the United States announced this week that the UK LTE broadband network for public safety that was to have been operational this year will not be ready for prime time until 2024 or 2025. Why is there a delay, when will it finally become live, and what will it offer the UK’s public-safety agencies?

First estimates for network operation were that the network would be ready in 2016, and then 2019. Both dates were missed and the Home Office signed an extension to continue to use the Tetra Airwave system with Motorola Solutions until 2022. The Home Office also indicated to Parliament that some elements of the Tetra Airwave network would be required through 2023. With the broadband Emergency Services Network (ESN) being pushed out to 2024 or later, it appears Tetra will continue to be used well beyond the 2022 contract date.

Fanfare for the UK public-safety network began more than a few years ago. In 2017, Urgent Communications published an article about the network going live in 2020 but making use of Land Mobile Radio (LMR). In the UK, this means using Tetra radio technology to provide off-network one-to-one and one-to-many communications. In that article, Urgent quoted the Programme Directory for the Emergency Communications Programme at the Home Office who stated that the LTE ESN would begin migrating users in the middle of the next year (2018).

Obviously, this timing was optimistic and in mid-2019, the Home Office revised its original estimate and announced that the “much delayed and over budget ESN will deliver a technical alternative to the existing Motorola Solutions-owned Airwave TETRA system within the revamped project schedule, Clark acknowledged that the timetable for convincing users to switch to the LTE solutions—and implementing it—is not as firm.”

The following quote should have given pause to potential public-safety users. “I think, technically, we’re really on track to get the meat of the program complete by the autumn of next year,” Clark said. “The real challenge that we face right now is building confidence in our customer base and demonstrating in the real world that this is up to the job, that people’s lives can be trusted with it, and that we have comprehensive testing—what we call an assurance program—that’s being finalized at the moment. It’s a major set of activities, a whole series of real-world tests before we go for at-scale deployment.”

The ESN will begin initial trials in the middle of July, with border officials using Motorola Solutions’ Kodiak Push-to-talk Over Cellular (POC) offering. The trial is slated to expand in December. Home Office officials are devising a plan to distribute all of the equipment needed to make the shift to ESN voice, assuming the early deployments go well, Clark said.”

Emergency Services Network (ESN)

Spectrum for the ESN is being supplied by cellular provider EE (formerly Everything Everywhere), a wireless and Internet provider that is part of the British Telecom Group. Motorola Solutions is responsible for the software applications as well as the POC application, which for now will be Motorola’s Kodiak solution that is not yet fully Mission-Critical Push-To-Talk (MCPTT)-compliant. The UK system is designed to replace the “expensive” Airwave Tetra system and not co-exist with it like FirstNet and multiple LMR systems in the United States. In the UK, the Tetra system is nationwide while LMR systems in the United States are licensed on multiple portions of spectrum, to cities, and to counties, resulting in a patchwork of LMR service. This patchwork is why Congress and the Executive Branch approved a single nationwide system (FirstNet). The Tetra system already provides nationwide interoperability for voice and the idea is to move all public-safety agencies to the new LTE ESN and close down the Tetra network. The glitch in making the LTE network the ONLY public-safety network is that even with ProSe (LTE off-network communications), public-safety users will not be able to communicate off-network inside buildings and when out of network coverage. This is the same reason the UK Home Office announced that when the LTE network is turned on, Tetra would still be used for off-network communications.

With the date for ESN operations pushed out yet again, this time for another four years or so, perhaps there will be more robust ways available to handle off-network communications using existing LTE spectrum. However, at the moment, I would not bet on LTE being capable of providing solid and reliable off-network communications. The UK plan to replace one nationwide network with another is different from ours and has implications beyond what we are doing here by keeping LMR systems in operation and overlaying FirstNet for nationwide PTT, data, video, text, and redundancy. Leaving existing networks in place rather than replacing them has proven to be a good solution for the United States where we have the FirstNet nationwide network. Turning off the Tetra nationwide network in favor of an LTE-only nationwide network presents the UK with a completely different set of challenges. As we move forward, we should be able to learn more about what to do and not do by observing FirstNet, the ESN, and other networks worldwide.

The Home Office seems to be well aware of many of the issues it will have to resolve. For example, it knows it must provide coverage for public safety even where there is no commercial coverage today, so it is “building extended coverage masts” that are owned by the state and will be used by EE as it builds out the ESN. What is not clear at this point is whether these same sites will also be used for commercial broadband to cover the areas where there is no commercial coverage. Another interesting aspect of the new public-safety LTE network is that it is being designed to handle helicopter traffic and air-to-ground communications up to about 10,000 feet. This means the network must be engineered to accommodate airborne units as well as land-based activities.

A document outlining the changes EE was requesting in order to be able to provide broadband communications for public-safety agencies in the UK was published in 2017. According to the Home Office, at the time there were approximately 300,00 to 350,000 first responders in the UK with 50,000 vehicles, 115 aircraft, and 200 control rooms. When EE was awarded the contract to build and operate the ESN, it agreed to build out at least 400 more LTE sites and make them available to other network operators. Further, the UK Government agreed to build out an additional 300 sites in the most remote locations of the nation and make them available to EE to provide 95-percent coverage of the UK.

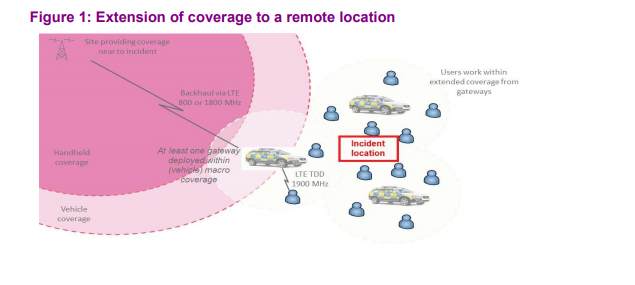

The ESN build-out is significantly different from FirstNet. First, some of the spectrum will be in the 1899.9 to 1909-MHz band using Time-Division Duplex (TDD), which means the uplink and downlink will share the same portion of spectrum with time increments. Those who used Sprint’s 2.5-GHz system in the United States know TDD is still full-duplex and it works well. The second portion of the assigned spectrum, 800 MHz/2.6 GHz, will be used in part to connect temporary base stations and to provide backhaul. The term “backhaul” is defined here as LTE backhaul to join temporary base stations and other devices back to the same network. (Report footnote 4:

“For the purposes of this license variation consultation, use of the term “backhaul” should be taken to

mean the connection between the ESN Gateway device and the main EE LTE access network.”

The Emergency Services Network Overview (Gov.UK), which was written at what appears to be the very beginning of the ESN effort, contains some interesting statements in regard to delivery of services, coverage, coverage assurances, extended-area service, and “ESN Products.” ESN Products include ESN Connect, which was billed as “fast, secure and reliable data connectivity for vehicles, allowing communications from other users to the mobile data terminal in the vehicle (for example, dispatch messages) and enabling other devices to tether and connect over ESN.”

There are also plans for ESN Connect+. “ESN Connect+ is a SIM-only voice and data plan that provides a fast, secure voice and data connection on the dedicated network designed for the emergency services.

Emergency services customers will benefit from the widest geographical coverage and bespoke service designed to meet their unique needs.

Customers in the emergency services will benefit from data prioritisation, which means the device will perform consistently when using data, even in times of high network traffic. It will also be possible to specify a higher level of prioritisation if needed for any critical applications.” This sounds like priority and pre-emption as we know it on FirstNet.

ESN Direct is billed as “A new generation of Push-to-Talk and critical messaging product on a smartphone,” but the rest of the description doesn’t really address off-network PTT communications.

Lastly, ESN Prime is a fully-comprehensive new-generation public-safety service on a smartphone. “It offers a full suite of public safety communications services including critical voice push-to-talk, messaging and video, and is aimed at organizations who are ready to begin the move away from Airwave.

One of the new features ESN brings is video, which will expand the capabilities of those working in public safety. ESN Prime incudes critical voice push-to-talk, messaging, video, public telephony, messaging and It also includes interworking and ESN mobile device management (Airwatch).”

Waiting for ESN

It is clear that the UK has looked long and hard at the idea of moving all public-safety agencies off Tetra and onto this new LTE network, and one has to assume that as the UK moves to 5G, the network will move to 5G. However, at the moment, there are more delays. Latest indications are that the Tetra network will remain active and in use until at least 2024 or 2025 because of these delays and, of course, off-network communications that meet the needs of public safety are not yet among LTE’s capabilities.

There are also new accusations of government failures and other shortcomings in putting the new network into operation. I have no interest in discussing these delays or why they occurred. You might remember it took the Oklahoma Bombing in 1995, terrorist attacks in 2001, and a number of damaging hurricanes to reach the point where there was a consensus in Congress (nudged along by the Public Safety Alliance and Public Safety Spectrum Trust) and a bill was passed to create FirstNet in 2012. After that, it took another five years of hard work by The FirstNet Authority and the public-safety community to issue a contract and begin building the network.

Other countries are also facing delays. Dwight Eisenhower said, “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” I think all of us involved with public-safety communications can relate.

I have to wonder who has been making decisions not only in the UK but in the US and elsewhere. Vendor companies are often far too optimistic when it comes to technology. Before FirstNet was even in the design stages, I remember an IACP convention where someone was hawking PTT over broadband as being a done deal. In fact, this demonstration was later used to convince some in Congress that LTE could and would soon replace all land mobile radio systems in the United States. The public-safety community had to work hard to undo the harm caused by that debacle and to make sure those who would be voting on FirstNet truly understood the issues.

FirstNet is a model for the rest of the world and I believe The FirstNet Authority is obligated to help other countries better understand the twists, turns, and bumps on the road to public-safety broadband. I feel our government made the right move when it created a specific band in the 700-MHz spectrum for public-safety use. Many countries are carving out portions of commercial networks and providing priority and preemption, and it appears that our own FCC has come to the same conclusion I did a while back when I wrote about mixing all types of communications on a commercial broadband network as not being the best approach. It seems that this FCC (but hopefully not the next FCC) feels as though everyone should be able to simply share commercial broadband spectrum.

My answer to that is today, FirstNet users do share LTE and soon 5G spectrum with AT&T commercial users. However, FirstNet users have priority and pre-emption on all of AT&T’s LTE spectrum including its 5G spectrum. As we are faced with more and more emergencies lasting longer all over the United States and network slowdowns partly due to work-at-home and school-from-home programs, it is reassuring to know that when the sh*t hits the fan, public safety has its own dedicated spectrum. If we are asked to share spectrum with all other users, any action in that direction should be preceded by careful consideration.

Only after the Secret Service, FBI, DEA, US Forrest Services, Border Patrol, and other Federal Agencies are directed to start using commercial networks, even on a priority basis, would it be appropriate to talk about public safety giving up its spectrum. In the meantime, we should be tracking any effects resulting from these agencies moving to commercial spectrum to determine whether sharing really works as those on the FCC Commission think it will. It would not be acceptable for those in the field to suddenly have to deal with the consequences of sharing spectrum.

As the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and others roll out their public-safety broadband networks, we will learn from the different approaches taken by different countries. I see the main issue in making sure public safety has the spectrum it needs today and access to more tomorrow is that the public-safety community in each country must be involved in the process from day one. While we might think having a democratic (small “d”) form of government is an advantage, our history of having to fight for our spectrum and then keep it requires that others be willing to listen to the end-user community before arbitrarily drawing up a plan and trying to make it work without buy-in from the users whose lives may, in fact, depend on their ability to communicate.

There is one final issue I believe to be important enough to raise again. Prior to FirstNet being approved, we ran tests in Alameda Country using its newly-installed 10 MHz of 700-MHz public-safety spectrum. The tests, which are published and available for review, focused attention on cell-sector congestion, which is more prevalent with public-safety agencies than commercial traffic. Many localized public-safety incidents require large numbers of public-safety vehicles and personnel concentrated in one cell sector. We were especially concerned about this when we were looking at having only 20 MHz of spectrum nationwide. In normal use, cell sites can accommodate large amounts of traffic over the network. However, when a heavy traffic load is confined to a single cell sector, as far as public safety is concerned, the “network capacity” is reduced to the capacity of that one cell sector. Users served by other cell sectors and sites are usually not even aware of a capacity shortage in an overloaded sector.

When AT&T won the FirstNet contract and made it clear that in addition to building out Band 14 it would make all of its spectrum usable for public safety, it took a huge weight off those of us who were concerned about sector-capacity overload. Most sites that provide Band 14 for public safety also have one, two, or three other portions of AT&T spectrum on the same tower so the load can be better distributed. At the same time, if needed, public safety can move to Band 14 and not be impacted by commercial users when it comes to total network capacity. Again, this is not about total overall network capacity, it boils down to capacity within a single cell sector or cell site.

Winding Down

Well, I think that is enough to digest for today.

Until next week…

Andrew M. Seybold

©2020, Andrew Seybold, Inc.

Like most systems of this size and complexity, the politicians and IT folks usually responsible for the project don’t recognize that implementation will take about ten years. I was Project Engineer on the Alberta First Responders Radio Communication System, a P25 voice only sytem with close to 400 sites. When I was hired in 2006 the target for completion was 2010. When I retired in 2013 construction was nearing 50%, and it was activated in July 2016.

This is one of the best Advocate columns I’ve read, I bet even some of the UK folks have a better picture of their own situation :). You touch on a lot of hot and very critical topics that broadband PTT over LTE users could face anywhere, particularly when it comes to off network. Many times we forget that the cellular networks can be prone to outages and not everyone has a multi sim device, so we will still need LMR as a backup even for cellular dead spots, not just for off-network.

With such heavy reliance on cellular networks today it can also become an Achilles heel in time of domestic terrorism or foreign invasion. One foreign adversary I recently learned has 9000 jamming devices ready to deploy anywhere they can drop them, to take a network down including their own. The major vendors now make multi-network LMR/LTE/Wi-Fi portable and mobile radios and I believe this will become the norm so they can work anywhere day-to-day. Now we just need a nationwide virtual PSBN that can roam over millions of Wi-Fi hotspots nationwide (like we currently have for Universities) with financial incentives for every homeowner and business to allow First Responders to roam on to their Wi-Fi. In-building coverage solved for the “most part”.

Again, Interoperability is a priority for First Responders. There needs to be a national plan for Talk Groups at every county level along with a national standard for Radio IDs and user aliases. The Interoperability TG’s need to be established on the IP side for apps then interconnected with current Interoperable radio channels (across all the bands). This stuff just has to work ad-hoc on-the-fly as roamers come on to the scene. This exists today within many PoC apps out there by just dragging a circle on the app’s map and everyone is connected within it. Now it has to happen between vendors, on a national scale, but again the TG’s have to be planned and established first. NPSTC is looking at some of this.

These IP Interoperability gateways should be cloud based over the Internet and really need to be network agnostic in order to work anywhere, which includes cellular (multi-carrier SIMS), WANS, LANS, WiFi and now satellite as LEOs are being deployed by the dozens monthly, until the earth is blanketed with thousands.

Lastly we need to discuss a very critical issue you mentioned regarding bandwidth capacity within a single cell cell site. This actually goes beyond public safety users to general users crowding into any area, particularly in rural areas during peak times like holidays. I’ve been on FirstNet for over three years and even with Priority and Pre-emption I’ve seen the network come to a crawl every 4th of July at the lake here. The first two years it became unusable. This year they added Band 14 which was a little better. I had to manually log in to the console and elevate our devices for the entire holiday weekend. I still only saw 1/4 the speeds we normally see with latency and jitter suffering. More than adequate for PoC traffic which was critical! However maps and weather were slow and video was hit or miss. The only way around this is 5G with more bandwidth available per user through all the different methods they deploy. You just can’t fight physics.